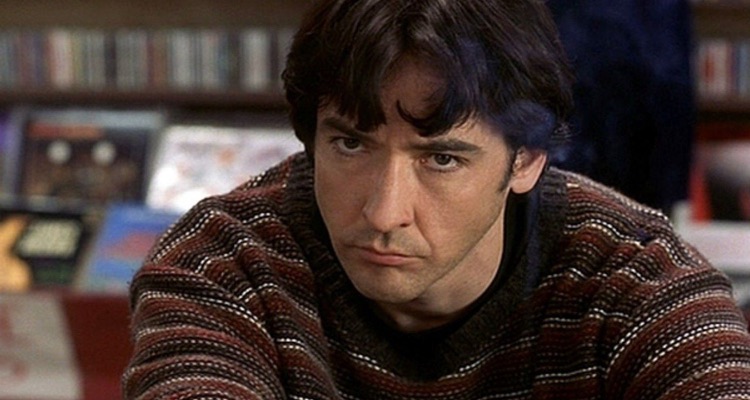

To me the enduring image of The Year of Living Less Dangerously remains John Cusack as Brian Wilson in bed, starting skyward, silent and paralyzed, the present merging with the past, the very walls shape-shifting about him.

In the biopic Love and Mercy and in life, Wilson lay in bed for years, afraid to leave. Outside, phantoms awaited. In a sequence reminiscent of nothing less than 2001: A Space Odyssey, Wilson, at middle age, sees himself as a young genius he once was, and then as a child. All of them locked in time, tethered together by fear and trauma.

“We’re ghosts. We’re phantoms,” says Andre Gregory to his dinner companion, Wallace Shawn, in My Dinner with Andre, another film I watched for the first time during the 12 months I stayed home. “What are we?”

What were we, really, during the most severe months of the pandemic but ghosts haunted the houses and abodes of our former lives, existing in a state of suspension, unable to return to the world we knew? In the particular circumstances of my own home detention, I turned to movies more than I ever had in order to stay grounded in my increasingly incorporeal existence. Film became the portal through which I visited other realities while struggling to remain grounded in my own.

All in all, I watched some 250 films between the middle of March 2020 through that same point this year. No doubt others watched even more. (I mixed in some “Columbo” and “Schitt’s Creek” for good measure.) I methodically kept a viewing log, something I had never done before. Why? I had no idea. It just felt important, even necessary.

There was no rhyme or reason to my choices. I stayed away from Contagion and Outbreak, thanks, and World War Z or I Am Legend — even my long beloved The Omega Man. Anything plague-related. No mutants. No monsters. One film sometimes would lead to me to its distant cousin. I watched Laura and the Eyes of Laura Mars in the space of the week, both set amid the glamor of old New York, both featuring lead actors with ethereal presences. Sometimes the connection was made purely by accident, as when I watched Knives Out and Cutter’s Way back to back. It’s only a shame I didn’t think to add The Razor’s Edge. There was Moonlight, Blood on the Moon, and Moonrise Kingdom in close proximity.

And often, my viewing sequence made no sense, as I veered from arthouse Scorsese with The Age of Innocence to second-tier Spaghetti Western with Red Sun to a romp in the sun with The Birdcage and finishing with Bergman’s Wild Strawberries.

Yes, there was an emphasis on comfort. I watched all those Columbo episodes for a reason. While it could have been an opportunity for me to really stretch my boundaries, I found those boundaries stubbornly resistant. I watched the classics by Bergman, Kurosawa and Welles and occasionally strayed out to watch something like Parasite or Da 5 Bloods. But was I scanning MUBI to check out the best of Czech or Indian cinema? Sadly, no. My circuits were already overloaded. Existence was an effort.

And so, I went to my shelf. I watched (again) Barbara Stanwyck tease and torture Henry Fonda in The Lady Eve, Sharon Stone cross and uncross her legs in Basic Instinct, Rebecca Ferguson sweep up the opera house stairs in that bright yellow gown in Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, Dorothy Malone catch Bogart’s eye in The Big Sleep. For years, particularly after my divorce, I had steadily built a collection of DVDs and Blu Rays – even as streaming overtook physical media as the delivery method of choice. And for years I (and some worried girlfriends) wondered exactly what was the purpose of all this?

Last year, the purpose made itself evident in a way I could never have anticipated. If one is to remain in one place for months, better to do so with an inventory of waking dreams. My shelves were stocked like a bomb shelter’s, but with film, not cans of discount tuna.

As the pandemic progressed, the initial jolt of energy that some felt being stuck at home (baking, bingeing, zooming) began to give way to a sort of malaise, as it become clear that this was nothing that was going to be resolved anytime soon. People on Twitter began to complain that they were running out of “content” to watch. There is nearly inexhaustible supply of movies going back 100 years, I wanted to tell them. But I knew better. The complainants were of a type likely to look askance at anything dating back past the turn of the century, much less to watch, say, Ford’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or Altman’s California Split. I was grateful though for those kindred souls on Twitter who were darting down their own cinematic rabbit holes. An odd, half-forgotten film, such as Phil Alden Robinson’s Sneakers or Spike Lee’s 25th Hour would suddenly find new life as viewers stumbled upon it and recommended it to others. Amid the isolation, I managed to locate some community.

My summer wasn’t going as I had planned. In my working life, I’m a political journalist, and 2020 was intended to be spent on planes, in cars, in cheap hotels and airport bars, covering the presidential race. There were no primary nights, no debates to attend, no post-convention parties. All of that was gone. The country was in upheaval. There were protests and riots miles down the street, in downtown DC. But I was at home — watching the coverage, yes, but also disappearing into Femme Fatale and Phantom Lady. More ghosts.

I worked, but remotely. Campaign events via zoom, debates via television. But there were still so many hours to fill. Some of it was occupied in the best way. My daughter, attending high school virtually, spending more time at home that anyone expected for her sophomore year. As the months passed, she became more interested in developing her own film education. Together, we watched Die Hard and Dirty Dancing. She wanted more of a challenge, so it was on to Pulp Fiction and Taxi Driver. I steeled myself for the adrenaline shot into Uma’s heart and DeNiro’s final bloody rampage, but she handled them with ease. Even with all the carnage in the world, she didn’t want to lose herself in escapism. That she ran toward the flame was heartening.

Last fall, when the weather turned cold, the election came and went without the then-president conceding and COVID cases spiked anew, was especially hard for me. So beyond Love and Mercy, there came other movies about men at sea. DiCaprio’s teen in hiding in Running On Empty, Kirk Douglas’ out-of-time cowboy in Lonely Are the Brave, Harry Dean Stanton walking toward parts unknown in Paris, Texas, Roy Scheider pushing his limit and beyond in All That Jazz, Forest Whitaker trying to survive with honor in Ghost Dog, Griffin Dunne at Manhattan’s mercy in After Hours, Paul Newman just trying to get by in Nobody’s Fool.

Nobody’s Fool, directed by Robert Benton, gently mocks the notion of grand plans, of a life of ambition.

“Doesn’t it bother you that you haven’t done more with the life God gave you?” Jessica Tandy’s Miss Beryl asks Paul Newman’s Sully.

“Not often,” he replies. “Now and then.”

Back to Cusack’s Brian Wilson in that bed. Here’s the thing about it. The movie – intentionally or not – was as much a tale of Cusack’s wayward talent as Wilson’s. It was a comeback of sorts for an actor who had, for an extended time, become the living symbol of young white male restlessness, from his Lloyd Dobler in Say Anything to angsty Rob Gordon in High Fidelity. (“The Rob Gordon” as Catherine Zeta-Jones said in her Chicago-via-Wales accent.)

But, in film as in life, you can’t exist eternally in a state of perpetual near-adulthood and so the Imdb filmography took one turn – into romantic comedy (Serendipity anyone? Anyone?) – and then an off-ramp into a lost highway of VOD thrillers and internationally financed productions with titles like airport paperbacks, The Frozen Ground, River Runs Red.When Cusack-as-Wilson is lying in bed for those months, staring outward in silence, whose past is he viewing? Whose potential is he mourning?

And here’s the other thing about it. Cusack and I are the same age and were born in the same place, Evanston, Illinois. I grew up in the Midwest—and he may has well have been me in Better Off Dead or One Crazy Summer. The year High Fidelity came out, I was bouncing around from career to career, city to city, woman to woman, looking askance at the world with same neurotic cynicism. When Rob settles down with his lawyer girlfriend at the close of the film, it seemed a signal. Dude, it’s time. I got married two years later. (Although it was clear then that Rob’s decision came with a degree of ambivalence.)

I think there’s a reason why Cusack couldn’t transform himself into a rom-com bf or action star. That restlessness, that side-eye never really went away. The contrarian response that defined him that was still firing but had no place in the world of responsible 30 and 40-year-olds, with people who have a plan. He couldn’t be cuddly like Paul Rudd and couldn’t be a simple-minded killing machine like Gerard Butler. He has too much on his mind.

I’m a lawyer by training, a reporter by trade, so I understand that the side-eye, that way of looking at the world becomes ingrained. So last year, stuck at home with COVID raging and world in repose, there I saw the original Beach Boy, Brian Wilson, lying in bed, looking backward, questioning whether he would ever be again the person he was, and there was John Cusack, the Gen-X prince, and there was me. I was the middle-aged, divorced Dad raising a daughter trying to survive both a pandemic and a turbulent industry, but feeling like a phantom. Denied covering the election, denied the road, I had lost my vibrancy. The work had long validated me and insulated me. One of the benefits – or hazards – of my profession is that with the deadlines, the travel, the late-night bars and the three-star hotels, there is little space to consider whether you ever should have ever realized your potential.

Now, there was just too much time to take stock if I had made good use of my talents even as I at times feared their slipping away. I would wake in the morning and stare at the ceiling, trying to recall what day it was. The walls closed in. I slept too much or too little. The future, whatever it might have been, felt behind, not ahead. Is this what it felt to be Brian Wilson or John Cusack – that the best of you had passed and the remaining challenge was survival and beyond that, sheer relevance? The hope of another act? And of course all the while I was mindful that these were problems of a certain kind, that I was fortunate for many reasons to be considering them at all.

The year turned. The election crisis faded. A new administration took over. I got vaccinated. Caseloads began to decline. Things appeared to be getting better. I watched movies about adults who were finding their way: Paterson and Wonder Boys and Nomadland and Mank. I wept over Tokyo Story. My daughter grooved to Gone Girl and The Graduate – two indelible pieces of pop-art and spent a few weeks abroad in France. I hope to screen for her Breathless and La Piscine and many other classics in the coming weeks. I still haven’t gone back to the office, still haven’t gotten back on the road. And now the virus is surging again. It’s enough to make me wonder if waking up, staring at the ceiling for years just like Brian Wilson did, will stretch through another fall and winter, with the same questions nagging.

I am still watching movies. I am still making lists (128 films in ’21, to date). And am waiting to move on from this state of semi-suspended animation. For all the love I have of film, I hope that time comes soon. Until that time, tonight I think I’ll watch The Razor’s Edge. — James Oliphant